Foreword

Climate change has gone from theory to reality. It’s already showing up in the weather floating above your head: extreme events are increasingly super-sized. The release of over a trillion tons of fossil fuel carbon and methane pollution—that’s one trillion hot air balloons of man-made chemicals since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution—is now spiking floods, droughts and heat waves. No, it’s not your grandfather’s weather anymore.

Sure, the climate has changed before, but this time around we can’t point to the sun or volcanoes or wobbles in Earth’s orbit. We are the volcano, and the exquisitely calibrated conditions favorable for not only our survival, but the fate of all species on the planet, are being stressed like never before. Global warming, pollution, deforestation, overfishing, acidification of the oceans and overdevelopment have already seen the world lose half its animal population over the last 40 years. A 2015 report in the journal Science examining 131 studies predicts that one in six of the Earth’s species will be lost forever to extinction if world leaders don’t take effective action on climate change.

If anything, climate models have been conservative: the volatility and disruption we’re already witnessing on a planetary scale exceeds even the most alarming predictions thirty years ago. And here’s the thing: in spite of a robust and rapidly-increasing body of data, evidence, and scientific validation, considerable uncertainty remains. Put simply: we don’t know what we don’t know. There will be tipping points nobody predicted in advance, discoveries that no computer model could anticipate. The reality: we’re running a dark, Darwinian experiment, not only on the atmosphere, oceans and cryosphere, but on Earth’s ability to sustain and nurture all life.

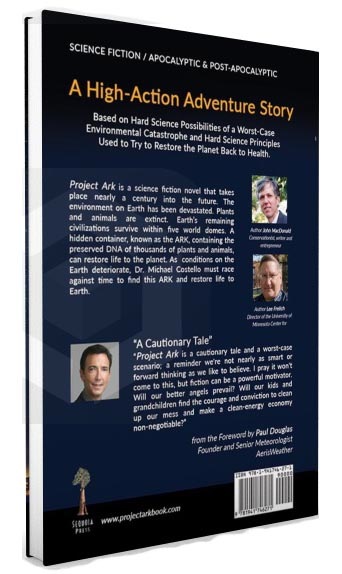

Project Ark is a cautionary tale and a worst-case scenario; a reminder that we’re not nearly as smart or for- ward-thinking as we like to believe. I pray it won’t come to this, but fiction can be a powerful motivator. Will our better angels prevail? Will our kids and grandchildren find the courage and conviction to clean up our mess and make a clean-energy economy non-negotiable? I’m still hopeful for the future, but we would all be well advised to pay attention. Take nothing for granted.

Man and every other species on Earth has benefited from the fruits of creation. Every form of life on this precious planet is counting on us to do the right thing.

– Paul Douglas Founder and Senior Meteorologist, AerisWeather June 14, 2016

Preface

When we first began studying how humans might best apply their advanced understanding of scientific principles to solve environmental problems, we quickly came to realize the importance of having both scientific and spiritual spheres working together rather than competing against one another. The need for such cooperation became even more apparent as we delved deeper into the question of who we are in terms of our specific duty of care towards our planet and its inhabitants. Our telescopes and space probes have allowed us to explore vast regions of outer space, gaining new insights into the nature and origins of our universe, yet these same investigations have made it increasingly clear that the greatest mystery of all is right here on our own planet earth—life. Whether life exists elsewhere in the universe may never be known. But for the moment, at least, and until evidence is found to the contrary, the presumption must be that we are alone.

This living planet of ours is like a beacon of light shining through the vast emptiness of space, and it is indeed humbling for us to ponder our stewardship role of this remarkable creation. But the beacon is beginning to flicker, and if we ever allow it to be extinguished, the loss would be irreparable. Earth has the unique ability to nourish all life found upon it and it is important for our survival that we respect all parts of this ecosystem. In recent times we have tended instead to value certain parts over others, the result being that the system has become unbalanced and the harmonious relationships that once existed among all living beings have become dangerously disrupted. A mass extinction, caused by human actions, is well underway. With the loss of biodiversity, the resilience of the Earth’s ecosystems to major disturbances such as climate change, and subsequently the ability of the Earth to sustain human life, is being reduced.

In the not so distant future, we may find it necessary to live in domed cities or to colonize nearby planets to ensure our survival. Under such dire conditions, we may be tempted to conduct high altitude geo-engineering experiments to re-set the atmosphere, regardless of the unpredictability and extreme risks involved in such projects. Then again, we might simply decide to hunker down and make the best of a bad situation. But in any case the most tragic consequence of all would be the loss of life’s unique relationship to our own planet Earth and in a broader sense to the universe.

We humans are resourceful by nature. When confronted by adversity, our imaginations and fortitude rise to the occasion. We thrive on challenges and often do best when the odds are greatest against us. Perhaps these same virtues will once again serve us well, but the road won’t be easy. Life is resilient and if we reach out and extend a caring hand, it will respond in kind and flourish once again. But in the meantime, we must prepare for the worst by collecting and dry-preserving DNA from as many plants and animals as possible, including those still found in the wild and those held in captivity. The same advanced methods should be applied to genetic material already stored in frozen holding tanks. Then, if conditions improve at some point in the future, we will be ready to reconstitute the DNA, thereby bringing numerous species back from extinction into a more hospitable world. For even if we believe there is only a slight chance our planet will lose its ability to support life, we would be negligent to avoid taking action while we still have the resources and access to do so. The time to build the ARK of the 21st century is now while conditions are still favorable, rather than later, when many species will have vanished and resources to save the rest will be harder to come by.

As Warren Buffet put it recently:

“If an ARK may be essential for survival, begin building it today, no matter how cloudless the skies appear. If there is only a 1% chance the planet is heading toward a truly major disaster and delay means passing a point of no return, inaction is foolhardy.”

Chapter 1

They worked quietly, methodically, yet with the unhurried intentness of a team of line chefs facing a long series of incoming orders. Racks of test tubes lined the counters, along with large brown bottles of solution and several digital microscopes. A walk-in freezer stood against the back wall. The set-up had a makeshift look and much of the equipment bore the logos of high-tech companies that no longer existed. Still, there was an unmistakable energy in the air, as if something serious and vital was underfoot.

As he worked, Dr. James Grace would occasionally emit a muted “hmmm” without knowing it. His wife, Laura, seldom responded. She was busy with her own work. And she knew the brief purring sound was merely the audible expression that accompanied the appearance of a small technical problem. Dr. Grace was good at solving such problems. He’d been working with genetic material for decades at the San Diego Zoo, cataloging seeds and preserving the cell cultures of endangered species.

During those early years, Dr. Grace (often referred to as Noah in the popular press) had watched the number of endangered species grow, and eventually become overshadowed by the list of species presumed to be extinct. As the climate crisis intensified, he’d become outspoken about budget priorities that exploited the entertainment (and revenue) value of a few large and exotic animals while neglecting the investment required to maintain a wide-reaching repository of genetic material. When the authorities decided the time had come to downsize the zoo’s preservation program even further, Dr. Grace had quietly established his own lab to continue his work.

From that time onward, his name appeared in the press less often, though as the environment continued to deteriorate due to rising air temperatures and mas- sive plankton die-offs at sea, it became obvious to many that something more needed to be done to combat mass extinction, and rumors began to circulate that Dr. Grace was perhaps already doing it.

But having seen first-hand how shortsighted (and self-interested) the Federation could be, Dr. Grace had little interest in working with them again. He maintained his independence, though his funding consisted largely of under-the-table contributions from wealthy donors. He was seldom seen in public, and as a means of deflecting serious interest in his work and even his whereabouts, he began to cultivate the “crazy Noah” image that the tabloids had created.

When government entreaties to recruit him went unanswered, and efforts even to find him fell flat, Dr. Grace saw his reputation suffer yet another mutation, from that of a semi-mythic Orpheus who could tame the animals—or better yet, bring them back to life—to an “enemy of the people,” who, according to government propaganda, knew many things that would be of great benefit to mankind, but kept them selfishly to himself.

As his public reputation declined and his life became ever more solitary, James drew strength from Laura, who kept him healthy, shared his vision, and helped him daily with his work. Steeped in the traditions of her Native ancestors, Laura never lost heart.

When Laura announced one day that she was pregnant, James was momentarily stunned, rather than overjoyed. It seemed to him that the clandestine life they were living, and the legal and perhaps even physical dangers they might meet up with at any time, were less than ideal conditions for childrearing. But that reaction was almost immediately replaced by one of glowing joy and anticipation. And after all, the work they were doing involved preserving the genetic material necessary to replicate, at some future date, plant and animal species that were disappearing from the landscape. How fitting, he mused, that they were also going to be nurturing a new member of their own species along the way.

When he shared these thoughts with his wife, Laura sighed, gave him an affectionate look, and replied, “Well, dear, you can think about it like that if you want to. The way I see it, we’re going to have a baby.”

During Laura’s pregnancy, the work went on much as it had before. They had plenty of genetic material at their disposal; the problem lay in prioritizing species, and then re-encoding the ones they deemed most important in such a way that they wouldn’t require expensive, high tech refrigeration to preserve over long periods of time. Magnetic coding wasn’t reliable in the long term; the Graces therefore went through the time-consuming process of sequencing and the re-synthesizing a copy of the DNA of each species on an electrochemical micro-array using error-correcting Reed-Solomon codes. To increase the durability of the coding and protect it from degrading effects of oxidation and humidity, it was encapsulated in silica microspheres. The result was a synthetic fossil containing the genome of a given species, that, if kept in a cool, dark place, might well remain viable for eons!

Aside from its durability, such microarrays had a second virtue: they were extremely small. Millions of them could be stored in a shoebox. Dr. Grace had devised a scheme for identifying which was which, but keeping order among the files added further time and labor to the project. With some common species they found it expedient to store and index seeds in the conventional way using test tubes.

The couple sometimes mused on the likelihood that anyone would be around at a later date with the wherewithal to resuscitate the myriad of flora and fauna they’d painstakingly preserved. But they didn’t allow such thoughts to undermine their daily efforts. Once a species was lost, it would be lost forever: the Graces were convinced there was no task more worthy of their talents and energy than preserving what they could of these remarkable life forms.

From time to time Dr. Grace would make a trip to a remote location where the newly created fossils could be stored out of harm’s way, making use of a business front in the guise of a detoxification firm. Each such journey carried a certain risk of discovery—small aircraft were not often seen crossing the desert wastes of central California. On the other hand, few observers were in a position to spot such a craft either, now that visibility was so poor and urban life had been confined to the interior of large, widely scattered domes. Better to make such transfers, the Graces reasoned, than to allow some government or rogue agency to seize all the fruits of their life’s work in a single, well-timed raid. Their subterranean lab was equipped with rudimentary video monitors and warning devices, though the work they were doing was fraught with so many contingencies that a government raid seemed no more worrisome than a serious earthquake or extended power outage.

Keeping such fears in the background, the Graces took pleasure in their daily work of processing and preserving the genomes of individual species. The genetic material all looked the same, but each plant and animal they worked on conjured images and associations—taxonomic, medicinal, environmental. Working on a mule deer, Dr. Grace was reminded of the acorns the animals fed on in the fall. A pinyon pine would remind Laura of the tasty nuts she’d eaten as a small child. Handling the DNA of a short-horned lizard, Dr. Grace would recall the research he’d once conducted on the mysterious pineal gland in the reptile’s forehead. Thus each day was an exercise in nostalgia as well a preparation for a future that neither of them could fully imagine. And each day, the baby Laura was carrying grew larger.

When the alarms went off, Dr. Grace was working on the leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea. He was in a reverie of sorts, imagining the time when that species had roamed every ocean and commonly lived for a century or more. The flashing red lights caught his attention, and he looked up the monitor to see armed men advancing up the tunnel toward the lab. Lots of men.

“Laura,” he cried. “They’ve found us!”

But Laura had seen the lights and was already loading her specimens into a large titanium box mounted on a wheeled carriage. Dr. Grace disappeared into the freezer and returned bearing another large container. Laura wheeled the box in his direction and he loaded the material inside.

Distant alarms had begun to sound, and a few seconds later they heard a loud crashing sound.

“That’s the gate going down,” Grace said. “It will hold them back for a while, though I’m sure they brought some plastic explosives. We don’t have much time.”

Laura ran from one table to the next, snatching the most important tubes and containers until the box had reached its capacity. Several test tubes fell to the floor with a crash, but she hardly broke stride.

Then they heard the explosion. Closer. “They’re through the gate.”

He glanced at the video monitor and said, “Too bad the tunnel didn’t collapse. I think we have two minutes maximum. Let’s get to the pods.”

Closing the titanium box, he wheeled it to the far side of the lab, where he pulled back a rug to reveal a large trap door. Opening it, he negotiated the ladder and manhandled the heavy box into the first of two small transport pods sitting side by side in the external bay. After helping Laura down the ladder, he revved up the first of the pods, then settled himself into the second pod to get it going.

When he engaged the ignition, nothing happened. Not a sound, a crank, a flicker. Just an ominous silence. Laura stared at her husband.

“It’s not working?” she said in disbelief, though she knew the answer.

“I’ll get it going. But there’s no time to waste. Yours is ready to go. Get in.”

“Don’t be silly, I’m not going anywhere without you.”

“You must,” he said, raising his voice slightly. “Think of the child.”

“—I think you can fit,” she said.

“—not possible...”

“I don’t entirely remember how these things work,”

she said in an anxious voice. “I should have joined you more often on your flights. You’ll have to show me.”

There was a pounding noise from the far side of the lab, and a muffled voice could be heard.

“This is Captain Erik Reyes, FF. Dr. James Grace! You are in violation of the federal statute 3-39.40. Open immediately or things will get ugly around here.”

Dr. Grace moved to the other pod, and as he passed his wife he took a small dreamcatcher necklace from his pocket and placed it in her shaking hands. “Just something I got for you.”

“Show me what to do,” she said.

The pounding on the door was growing louder. James lifted open the cockpit, climbed in, and said, “Watch this. Basically these two upper left—” he flipped a few switches, and the pod surged, ready to depart, “—and then to engage prior to acceleration, this one. Press this and the autopilot will take you straight to the airport.”

Feigning confusion, Laura reached over her husband and pressed the button. She then slammed the hatch down, trapping her husband inside the active pod.

Rings of electromagnetic discs began to rotate as the pod levitated and began to pick up speed, with Dr. James Grace looking desperately, impotently back at his wife.

As he vanished, Laura could read her husband’s lips: “Laura! Laura! Don’t do this!”

“Goodbye, James,” she replied softly. “Techihhila.” (Lakota for ‘I love you.’)

Fastening the dreamcatcher hurriedly around her neck, Laura slid the rug back over the trap door just as the door on the other side of the room smashed apart.

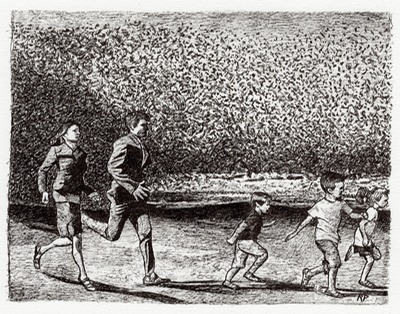

The ever-zealous Captain Reyes was in the lead. A shiver ran down Laura’s spine as she caught sight of him. He hadn’t seen her yet. But then he turned. Too late she slipped behind a pillar, as if by keeping silent she could keep her location secret a little longer. Then she began to run.

“There!” Reyes shouted, pointing in the direction of the sound. Laura could hear the oddly soothing sound of the stunguns as the soldiers fired wildly in several directions. The gunshots were like a series of smooth stones plunging into the water at the best possible angle to avoid making a splash. Pfftt. Pfftt. Her heart racing, Laura wove her way through a collection of life-sized replicas of gorillas. A flake of plaster splintered off one of the apes as a dart grazed it. The statue teetered in the opposite direction and then toppled over, smashing to pieces on the concrete floor of the lab.

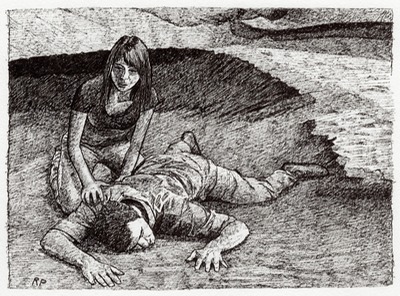

Though she knew running was futile, adrenaline and instinct kept Laura moving ahead. When she reached a wall of fiberglass rock just beyond the primates, she leapt through a gap that had opened in the long-disused material due to the explosion. She was outside! Brown smog covered the orange-red horizon. It was difficult to breathe in the scorching hot air. Laura leaned against a tall metal cylinder bearing the image of a blue whale and a sign: “Cryogenic Embryo Bank. Common Name: Blue Whale. Scientific Name: Balaeoneptera musculus. Status: Extinct 2055.” Though her pursuers were closing in, Laura continued to run past dozens of similar tanks. Finally she reached a place where she could look out over the distant ocean. Pfftt. Pfftt. She felt a powerful stinging in her ribs under her left arm.

As she began to lose consciousness, Laura could see, off in the distance, a droid-like elliptical craft gliding silently out over the water.